–Dorianne Laux

Monday, November 26, 2012

Monday, November 19, 2012

Monday, November 5, 2012

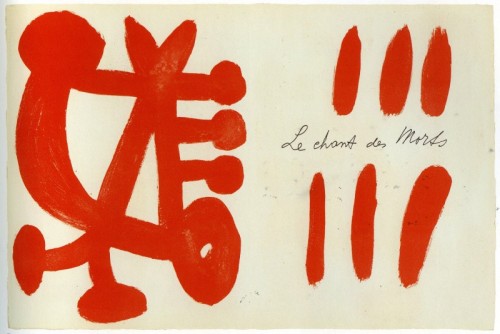

Le Chants des Morts - The Song of the Dead

.

Printed in one volume, size 42 x 32 cm

Manuscript of Pierre Reverdy, with Pablo Picasso

123 original lithographs, printed in red

Published on ‘vélin d’ Arches’ paper:

- 250 copies, numbered 1-250

- 20 copies, off the market, numbered I-XX

Pierre Reverdy, one of the most important modern poets of France, and the Spaniard Pablo Picasso, the most versatile, innovative and productive artist of the 20th century, worked together and produced this excellent book.

Reverdy filled the pages of the book with his calligraphic handwritten poems (The Song of the Dead, 1946) expressing his personal intellectual doubts and feelings. Then, Picasso applied the strokes of his vibrant red-coloured brush, full of expressive motion, to these beautiful and luxuriant pages.

The result is a harmonic unity, which is created by the drawing that surrounds and passes through the text. Even so, it does not overpower, but supports it. In this way, a perfect amalgamation of text and image is achieved. The book appears to be a kind of improvised dialogue; something like a friendly chat between a poet and a painter.

Pablo Picasso was troubled for a long time about the way in which he would artistically express the poems of Reverdy. At the beginning, he drew some ‘traditional’ illustrations. However, he soon felt the need to match, somehow, the writing of the poet and its sculpting qualities with a relative, accompanying support.

Considering the impact of reality, he frees and exposes it to every useless and meaningless idea; then, by using the process of elimination, he brings it back to its meaningful elements. He does not simply try to harmonise his drawings to the text of the book.

In reality, he radically renews the relationship between the writings and the painting; he enriches it, giving it a new personal meaning.

.

via datura

.

Sunday, November 4, 2012

.

LONDON (AP) — Archaeologists excavating near Cambridge have stumbled upon a rare and mysterious find: The skeleton of a 7th-century teenager buried in an ornamental bed along with a gold-and-garnet cross, an iron knife and a purse full of glass beads.

Experts say the grave is an example of an unusual Anglo-Saxon funerary practice of which very little is known. Just over a dozen of these "bed burials" have been found in Britain, and it's one of only two in which a pectoral cross — meant to be worn over the chest — has been discovered.

One archaeologist said the burial opened a window into the transitional period when the pagan Anglo-Saxons were gradually adopting Christianity.

"We are right at the brink of the coming of Christianity back to England," said Alison Dickens, the manager of Cambridge University's Archaeological Unit. "What we have here is a very early adopter."The grave, dated between 650 and 680 A.D., was discovered about a year ago in a corner of Trumpington Meadows, a rural area just outside Cambridge that is slated for development.Dickens said the teen's grave was interesting because it had a mix of traditional grave goods — the knife, as well as a chain thought to hold a purse full of beads — along with a powerful symbol of Christian devotion.The grave, she said, indicated "the beginning of the end of one belief system, and the beginning of another."The teenager's jewelry — a solid gold cross about 3 1/2 centimeters (1 1/2 inches) wide, set with cut garnets — marks her out as a member of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy. She was about 15, but her skeleton hasn't yet been subjected to radiocarbon dating or isotopic analysis. Those techniques might help experts determine where and under what circumstances she grew up.Howard Williams, a professor of archaeology at the University of Chester who is not connected to the discovery, said bed burials were very rare. He noted that they were an irregular feature of wealthy female graves in England and mainland Europe, suggesting that Anglo-Saxons may have looked across the Channel for inspiration."It's part of a broader pan-European elite identity in life and in death," he said.

Three sets of Anglo-Saxon remains were also found nearby, but it's not clear to what degree any of the people buried there were related. As for the bed itself, there's little left of it other than its iron fittings.The rationale behind bed burials remains a matter of speculation.

"The word in Old English for 'bed' and 'grave' is the same because it's 'the place where you lie,'" Dickens said. "It is interesting that you have that association. You're lying there — but just for a much longer time, I suppose."

.

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Down (excerpt)

.

You want to wash yourself

in earth, in rocks and grass

What are you supposed to do

with all this loss?

—Margaret Atwood

.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)