My father, Dave Robert Shepard Sr., died on either December 30th or December 31st, depending on what time zone you were in. I received the call on the 30th at 11:30PM in Los Angeles, but the caller, positioned in Detroit, was two hours deep into the 31st. He was dead at 62 years old. Small cell carcinoma was to blame. It originated in the lungs and then travelled with great speed to all corners of his body.

I had been back to Detroit just six days before and was disappointed I couldn’t be with him at the actual finish line. We were partners. We had taken on this cancer project together. He chose me to deal with all the doctors and creditors and landlords. It was the only project we ever teamed up on. We never built a tree house or a soap box derby car together, but you would have never known it by watching us tear through chemo decisions and radiation plans. We were two great minds with one single thought: get into the end zone gracefully.

He had noticed a lump in his neck in August. A biopsy was taken and some chest x-rays. “A mass” was detected on the lungs. Those were his words to me, “a mass,” which sounded much more like the words of a doctor than the retired car salesman that he was. He was much more prone to use the word “fuck,” and I wondered while he was telling me this news if he realized how serious that word was. Test results from the “lump,” which turned out to be a swollen lymph node, came back positive for cancer. It was the phone call you see on TV and in movies. It was happening to me now, and I found the timing to be exceedingly inconvenient. In movies, news of this kind seems to always coincide with a huge hole in the lead character’s schedule. He or she is able to spend vast amounts of time at the bedside of the loved one, or at a diner having coffee and pie with estranged family members. This flexible schedule allows for some high quality catharsis to take place.

I was acting full time on a TV show based in LA when I got the call. He was in Detroit. On my days off from the TV show I was traveling around the country promoting a movie I had directed. During the month of August I went to Portland, Seattle, Chicago, Detroit, San Diego, Nashville, Memphis and New York. Compounding all of this was the recent and incredibly fortuitous news that my wife and I were pregnant with our first baby. Whoever was writing my life couldn’t figure out which storyline they wanted to tell, and decided to tell them all at once.

As tends to happen in real life, despite it being inconvenient, it all worked out. Pockets of time opened up here and there and I was able to go back to Detroit often. My initial response was to get him to do chemo in LA. Surely the weather would be better. He wasn’t having it. I then made a strong push for him to go to Oregon to be with my brother. Nope. He was staying in Detroit. He had a huge support system of friends there, and in the end, it was the right decision.

His friends. This is relevant. One of the few upsides of my father being dead is that I can now break his anonymity and state plainly that he was a proud member of Alcoholics Anonymous for over 25 years. During that quarter-of-a-century span, he accumulated the most colorful, caring, fucked-up group of friends you’d ever want to see. It was a rag-tag band of misfits bound together only by their shared desire to not get loaded anymore. What a group. It was truly his greatest accomplishment. They all loved him in a way that even my brother and I had a hard time doing. He hadn’t missed any of their birthdays or soccer games, and they saw only the man who had helped so many struggling folks get sober. They were by his side, uninterrupted, from diagnosis to death. Often annoying, but always a blessing, they gave him the greatest gift possible: their time. He was never alone. Not for one second.

When I visited we would break up the chemo routine with trips to the cineplex or restaurants of his choosing. He loved to eat. Holy shit could he eat. Of all of his addictions, and there were many (drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, sex, cars, houses, shiny things), eating was his number one. He never did get a handle on that vice. He could hunker down in front of the TV for hours, nibbling with comma-inducing ferocity the entire time. Nothing in the pantry was safe. He would come up with the most counter-intuitive combinations of food. Like a true alchemist, he’d put salsa on oatmeal, or smother frozen waffles with a can of black beans. He was like a perpetually stoned, pregnant woman. No permutation of ingredients was out of the question; anything was possible. It was a sight to behold.

We had a lot of fun together during those four months. We took long car rides through the back roads of rural Michigan. We spent a weekend visiting every single house and apartment the two of us had ever lived in. There were 28 between the two of us. Together we had only shared three of those places: a single-wide mobile home from 0-1 years-old, a small, brick ranch on a few acres in the middle of nowhere from 1-3 years-old, and a modern, middle-class home in a McMansion-ee neighborhood from 15-16 years-old. It was that gap between 3 and 15 years-old that caused most of our issues. He was a selfish asshole, and I lived to hold a grudge, so it was a thoroughly symbiotic pairing. The car rides proved to be shockingly therapeutic. One of the hidden benefits of cancer is that it can erode grudges the way WD-40 dissolves rust. It just finds it’s way into all the nooks and crannies and starts loosening. Before long, the once formidable chip on my shoulder had melded into something the size of a nicotine patch. Apologies were exchanged. Tears were had. Hugs were frequent and lingering. I spent the majority of our time together running my hand lightly over the tiny little hairs peaking out from the back of his soft, bald head. He let me do that for hours. Without any awareness of it at the time, the trips home turned into a proper Alexander Payne Movie. It became one of the more beautiful experiences of my life.

Things got worse, as they do. Car rides gave way to hospitals and senior care facilities. His last two months were spent dealing with cancer, heart disease and gout. He had an increasingly difficult time walking and spent most of his time in bed. On my last trip home, just before Christmas, I took him on his final jailbreak. I threw him in a wheelchair and rolled him through 20 degree weather to his favorite restaurant, where I watched him pick at his waffles and bacon. He couldn’t have had more than four bites over the course of an hour. It was a very clear signal to me that the end was near. I took him, for the last time, to his house. I gave him his percocet and sat him in front of the TV. He held the remote in his right hand like a six-shooter, splitting his attention between the TV, the view of the lake through the sliding glass door, and me. It was wonderful. We sat that way for over three hours.

I took him back to the hospital right around dinner time. They brought him a full meal, complete with dessert. He didn’t even touch the dessert. I never thought I’d see that. I had always imagined he would be chewing WHILE he died. When the nurse came to get the tray, my father thanked her and then went straight into his normal schpeel about taking her to the movies and maybe dancing. These invitations were always laden with less-than-subtle, yet just-charming-enough, sexual innuendoes. I had seen this fearless maneuver millions of times since I was a boy. My brother and I were routinely embarrassed by him at Big Boy’s, where he would tell female servers they had “nice assets.” We would hide our faces in shame as he flashed his warm, sincere smile. Shockingly, these gals often blushed or said something flirty in return. Now, I don’t think that is a testament to my father’s sex appeal as much as it is an indictment of Big Boy’s monotonous work environment, but regardless, he did manage to get away with murder, and that deserves some recognition. And as hard as it is for my brother and I to accept, he did have a “way with woman.” He did date, and sometimes even marry, women vastly outside of his pay grade (said the pot to the kettle).

The next day I showed up to the hospital to find that he had taken a very sharp turn for the worse. It was not what I was expecting. I had let myself believe that the fun we had the day before was some kind of magic antidote. I half expected to see him eating a full breakfast when I walked in, but instead he was dazed and motionless. He could no longer sit up on his own, and talking was proving to be too much for him. So we sat quietly. I climbed in the bed with him and rubbed the little hairs on the back of his neck. I squeezed him. I’d never seen him so cute and little. He was a 250 pound baby. We spent most of the day that way.

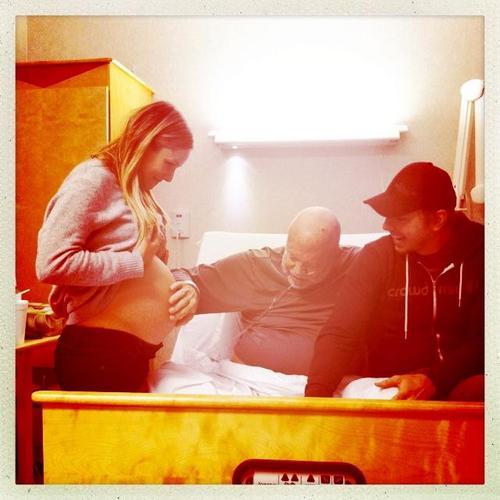

At one point, and unbeknownst to both of us, my wife walked into the room. She had flown in from LA without any warning. It was a surprise. It was an amazing, incredible, perfectly timed surprise. She lifted her shirt up and he put his hand on her swollen stomach. He left it there for the better part of an hour. He was smiling from ear to ear, sitting contently, unable to put together a sentence, but still capable of connecting to the new family member we were creating. He wasn’t going to make it to the birth, but that didn’t get in the way of him meeting the new baby. It was an emotional and triumphant moment. One I will never forget. If I live to be a thousand, I will still be in debt to my wife for giving him that one last thrill.

But there was still another thrill left to be had. One that is equally memorable. Just as day was turning into evening, the nurse came in to assist him with his pee jug. She was manipulating his penis into the mouth of the jug when he mustered up the strength and focus to say something pervy into her ear. It was too quiet for me to make out the whole sentence. I heard snippets of words and then, “…when I get out of here…” and then more snippets followed by her laughing and giving him a playful nudge. I couldn’t believe my eyes. He could barely muster a “hello” when I came in, and here he was waxing poetically to this 20-something stranger. As she walked away, he was smiling like a teenager behind the wheel of his first car. My normal reaction would have been to defend the poor nurse’s right to work in a harassment-free environment, but on this day, I was just too shocked by the eleventh hour show of virility. Here was a man, a bona-fide food addict, who had lost his will to eat. He couldn’t walk, and up until then, had stopped talking. He was wearing a diaper for Pete’s sake. But here he was, horny as hell and ready to party. It was his only vital sign still thriving. It was indomitable; impervious to the suite of diseases ravaging his body.

Witnessing the sheer power of that drive was eye opening. It put a few historical things into perspective for me. If this force was stronger than my Dad’s will to walk, talk, use a toilet or EAT, surely it was strong enough to lead Kennedy, King, Haggard and Clinton into the weeds. This was some powerful shit we were dealing with here. Putting the moral implications to the side, the strength in and of itself was astonishing. It almost deserved a round of applause.

I left the following day. I got updates from my uncle on Christmas and the four days that followed. Each was progressively worse. The light was getting dimmer and dimmer. He was slowly transitioning to whatever is next. Through all of those updates, there were no reports of pain, seizures, or bed sores. Only accounts of gently drifting away. And so it was, that on December 30th or 31st, we made it pain-free and with grace into the end zone; a feat that, as I write this, overwhelms me with gratitude. Our first project together was a total success. My only regret is that we didn’t take on more together.

Sunday, March 24, 2013

from Dax Shepard's blog, worth a read

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)